The Story of the Story:

How A Thing Done Came to Be

(first published in the blog Royalty Free Fiction, December 2, 2012)

A Thing Done started life as a footnote. Several footnotes, actually – one in a translation of Dante’s Inferno, others in history books covering the 13th century in Florence. And as I threaded my way through all these footnotes, I often felt I was working backwards from the end of the story, looking for its beginning.

At first what caught my eye was this: “The vendetta against Buondelmonte was the origin of the Guelf and Ghibelline factions in Florence.”

Well, that division was no small matter. It colored politics – not just in Florence, but in all of Italy – for well over a century, and vestiges of it remained in place several centuries later. To this day, Italian cities can be classified as used-to-be-Guelf or used-to-be-Ghibelline (or, not infrequently, used to be one and then the other). You have only to look at the crenellations on castles and public buildings: square crenellations mean Guelf, swallowtail crenellations mean Ghibelline.

So how did a vendetta against one man get all of this started? First let’s set the scene.

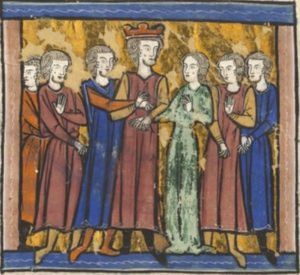

Florence at the beginning of the 13th century was bristling with violence – hereditary enmities, power struggles, deep resentments. The city was a commune, with no king or duke or other titular head. Her ruling class was formed by members of the ancient noble families, but also by wealthy bankers and merchants – an oligarchy made up of men of substance and influence, who commanded a certain amount of private military might. Florence had her share of knights, men with superb military training and ability, and they didn’t share their power easily.

Clearly, Buondelmonte was on one side and those who sought his ruin were on the other. Further reading told me that Buondelmonte had been betrothed to a woman of the Amidei family (the other side), and had broken off the engagement to wed a woman of the Donati family (his own side), and that the Amidei and their allies were so incensed at this insult that they called for a vendetta against Buondelmonte.

The story was getting more interesting. But I didn’t quite understand: if feelings were running that high, what was Buondelmonte doing getting himself betrothed to a woman of his enemies’ clan? Especially if she wasn’t really the woman he wanted to marry?

More footnotes, more reading. As I suspected, it wasn’t that simple. It usually isn’t. Buondelmonte had been forced into that betrothal as a result of an altercation that took place at a banquet. He had answered what he perceived as an insult from Oddo, one of his enemies, with violence, resulting in a knife wound to Oddo’s arm. Eventually, as was a custom of the times, a marriage was offered to make peace between the factions. Not a marriage he chose; not a marriage he wanted.

This was beginning to sound like a story I wanted to write. But what, I wondered, started it all? What did Oddo do that got Buondelmonte so enraged?

Past the footnotes now and deep into the contemporary and near-contemporary chronicles, I finally found what looked to me like the point of origin. At that feast, which took place to celebrate a knighting, a jester snatched a plate of food away from Buondelmonte and his dining companion. Was he acting on orders? If so, whose?

Buondelmonte’s companion was outraged, and Oddo took the opportunity to mock him and make fun of him because of it.

The companion told Oddo “You lie in your throat!” (yes, it really does translate that way: “Tu menti per la gola!”), but it was Buondelmonte, impetuous and hotheaded, who pulled a knife and then drew blood. And drawing blood was an insult too serious to overlook. So yes, it was a story. And I tried to tell it, writing of the conflict between Buondelmonte and Oddo, and of the two women from noble families, and of the mother of the Donati girl, who was said to have goaded Buondelmonte into forsaking his unwanted fiancee to wed her lovely daughter instead.

But I couldn’t stop thinking about that jester. The one whose prank had started the whole thing, and had plunged his city into near civil war. What was this experience like for him? How did he feel? What did he do? How did the resulting chaos affect him?

And when I found myself writing about the jester walking home late that night, I realized I had no idea where he lived, or how, or who he lived with. I didn’t know who his friends were, who he would want to tell about what had happened, what would worry him, how this incident would change his life. And I wanted to know.

So it became the jester’s story, and the story of his friends and neighbors. Buondelmonte and his quarrelsome friends and foes are still there, as are the women, but the story unfolds as the jester sees it. And it is richer for that; even the truculent nobles and their ladies are more fully developed for being seen through the eyes of one of their least imposing contemporaries. Especially the ladies, who lived in a society that allowed them very little initiative, but who were perfectly capable of making things happen from behind the scenes.

And the jester was so insignificant that he was in a position to see it all.

My jester is a man of the lower classes, living by his wits. He has no power, clout, or rights; he’s marginalized in a society that didn’t think much of self-employed performers. But for all that, he’s a man who makes sharp observations and has plenty to say. I believe readers will agree that he was the right person to give voice to the story.