For my newsletter of March 15, 2022, my friend and fellow author Alana White joined me to chat (or fare quattro chiacchiere, as we say in Italian) about Florence. We touched on some of the differences between medieval Florence (which I wrote about in my first novel, A Thing Done) and Renaissance Florence (which Alana has written about in two novels, The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, soon to be re-released, and The Hearts of All on Fire, a prequel to her first book, which will be released in a few months).

Here we are, Tinney Sue Heath for Team Medieval and Alana White for Team Renaissance, with our beloved city in between us:

I suppose we’d better define our terms before we get started. So for our purposes, when do the middle ages in Florence end and when does the Renaissance begin? My books are set in Italy in the early 13th century, which is pretty solidly medieval, and Alana’s are in the late 15th, which is Renaissance. But there’s something of a gray zone in between. Arbitrarily, let’s make our dividing line the end of the 14th century. With that in mind, here we go:

Alana: The first word or phrase that comes to my mind when I think of the Italian Renaissance is beauty. Not greed, vendetta, or Machiavellian politics. Together, my protagonist, the real-life lawyer, Guid’Antonio Vespucci, and his nephew and secretary, Amerigo Vespucci, lived when educated, fifteenth-century Italians already spoke of the “rinascimento,” when a new spirit of rebirth in life, art, and literature prevailed. Nowhere was this more evident than in Florence, at the time a city of about 50,000 souls.

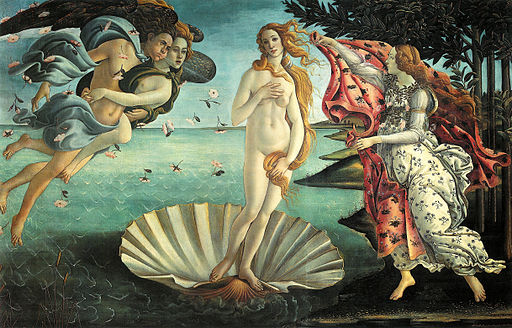

To me, there is no better illustration of this than the secular paintings of Sandro Botticelli (1444/45-1510), whose portrayals of dancing maidens in gauzy gowns, for example, set the bar for beauty, one that still holds. Sandro’s Primavera and Birth of Venus certainly were a far cry from medieval art.

Tinney, if you had to choose a word for medieval Florence, what would it be?

Tinney: Turbulence, I think. That may not sound very appealing, but in that agitation were the seeds of the Renaissance. While medieval art had nothing like Botticelli’s graceful figures, those dancing maidens might never have been possible had it not been for Giotto moving away from static, iconic representations of people toward a more solid, realistic depiction of actual human beings in actual space.

And in literature, Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch, all medieval, were still forces to be reckoned with in the Renaissance and beyond.

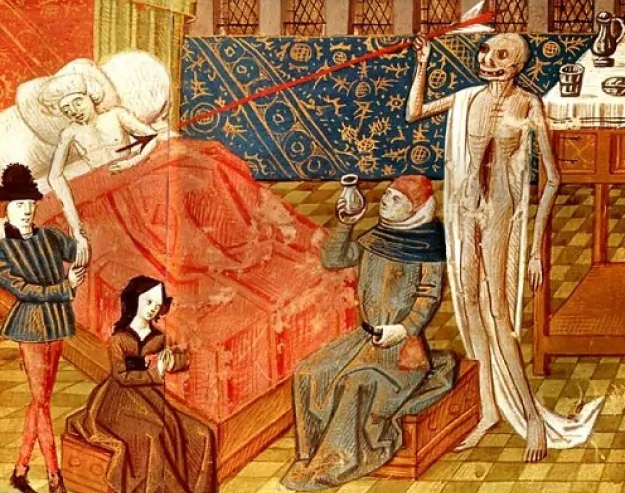

Many readers may not realize that Florence was much more populous in the middle ages than she was in the Renaissance. So many people moved from the nearby rural areas into the city in the 13th century that the city’s population tripled or even quadrupled, reaching a peak of 120,000. But then, in 1348, the Black Death killed somewhere between a third and a half of the Florentine people.

So while it’s true that medieval Florence was crowded, dirty, noisy, chaotic, malodorous, pestilential, dangerous, and politically volatile, it was also where the action was. It was teeming with life and color and creativity and passion and opportunity and ambition–in short, with all things human. There were reasons all those people wanted to try their luck in the city.

Alana: Your mention of Dante made me sit up straight! The title of The Hearts of All on Fire (1473) is borrowed from Dante’s Divine Comedy. “Avarice, envy, pride, three fatal sparks, have set the hearts of all on fire.” Yes, Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch were tremendous forces in the medieval and Renaissance eras–and they remain so today. (Think Dan Brown’s contemporary thriller, Inferno.) But jumping from the plague of 1348 to the glittering 1470s is a mighty leap. How did we get from the so-called Dark Ages to Florence’s glory days? In the 13th century life was more about sheer survival, I think, particularly after the Black Death. People were just grateful to wake up each morning and breathe.

Tinney: I think the plague was probably what caused that leap. With half the workforce suddenly gone, the surviving workers found themselves in a much improved bargaining situation for better wages and working conditions. Feudalism would never be the same. Whole families had been wiped out, so substantial bequests went to religious and charitable institutions. Slavery, formerly in decline, re-emerged as more laborers were needed. Rapid change was everywhere, in every aspect of public and private life. More people married earlier and more children were born, as if the world was trying to regain something of what it had lost. It was a difficult time, but a time when anything could happen.

Alana: The years immediately following the plague were miserable ones for Florence. While, as you say, surviving workers found themselves in an improved bargaining situation for better wages, the cost of goods more than doubled. Gloomy sermons preached the shortness of life and the eternity of hell. Some believed the end of the world was near. Add to this strikes and riots between the Guelfs and the Ghibellines (anti-union/pro-union) and a bloody tug of war between who would hold office in City Hall and who would not. Then–sound the trumpets, please!–at the height of this hair-pulling, in the early 1400s there entered Cosimo de’ Medici, a tremendously wealthy banker who, unlike the men in control of the Republic, preferred peace and quiet to government bickering.

Grumbling about the “party” currently in power, Florentines remembered how during the bloody guild riots, the leading man in City Hall had sympathized with the “Little People.” That man was Salvestro de’ Medici, and the unassuming, book-loving banker Cosimo was his relative–a distant one, yes, but family is family, and they were united in blood.

Wool, banking, wealth, and likability. All came together now to set the stage for the Medici dynasty. The family, you might say, was moving on up.

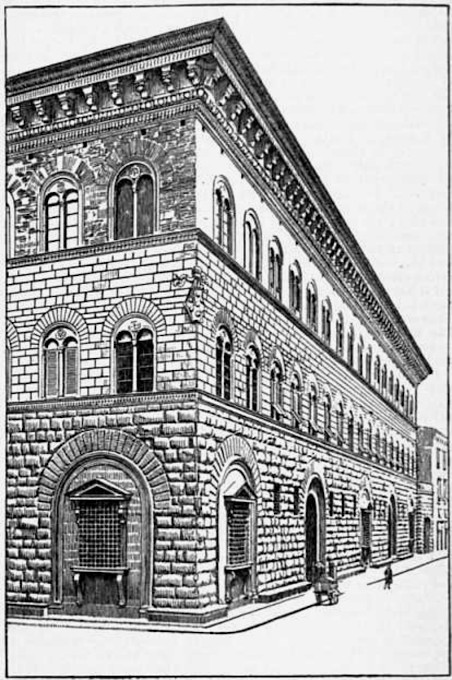

Of course, Cosimo did have political enemies–enemies who jailed him and exiled him, only to see him return home (in 1434) more powerful than ever. From that time on Florence pretty much belonged to the Medici family–between attempts to kill them, of course, Hence the meat of my stories. Anyway, it was Cosimo who had so much to do with the dawn of new learning, bringing scholars to town and collecting rare manuscripts, renovating San Marco, and so on. At the same time a building boom was happening. Cosimo himself built Palazzo Medici–but only after downsizing the original plans in a move to not draw too much unwanted attention to himself.

If this is understated, one wonders about the original concept!

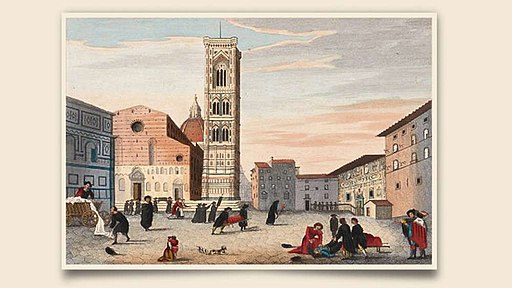

It was not all down to Cosimo de’ Medici, though. Many other wealthy Florentines were commissioning paintings and sculptures from the leading craftsmen of the day and building new, bigger, better homes for themselves and their families. Like Palazzo Medici many of them still stand in Florence today. Highly symbolic to me is that in 1473 Florence Cathedral finally was completed–an endeavor of two centuries. So! Overall, this was a time when people were stepping out of the darkness of the middle ages into the light of the Renaissance, moving from medieval to modern–or so it seems to me. Tinney, I suspect you might have a different take on this.

Tinney: Perhaps not so different, Alana. In many ways the medieval city was a dark place, literally. Narrow and winding streets were crowded with people and animals, and the sporti or little balcony extensions people built on upper floors of their homes, to expand their limited living space, jutted out over those streets and blocked the sunlight. Glassed windows were a thing of the future, so shutting out the weather usually also meant shutting out all or most of the light. The wider, straighter streets and open piazzas of the Renaissance were yet to come.

In the Florence of 1216, seen in my novel A Thing Done, the vicious wars between the Guelf and Ghibelline parties were just getting started. In fact, that’s what the book is about. But that conflict added its own kind of darkness to the next couple of centuries, as each party tried in turn to discredit, bankrupt, and exile the other. By the way, you say the Guelfs were anti-union and the Ghibellines pro-union, but in an earlier time it was more that Guelfs were pro-Pope and Ghibellines were pro-Emperor. Though it was never anywhere near that simple.

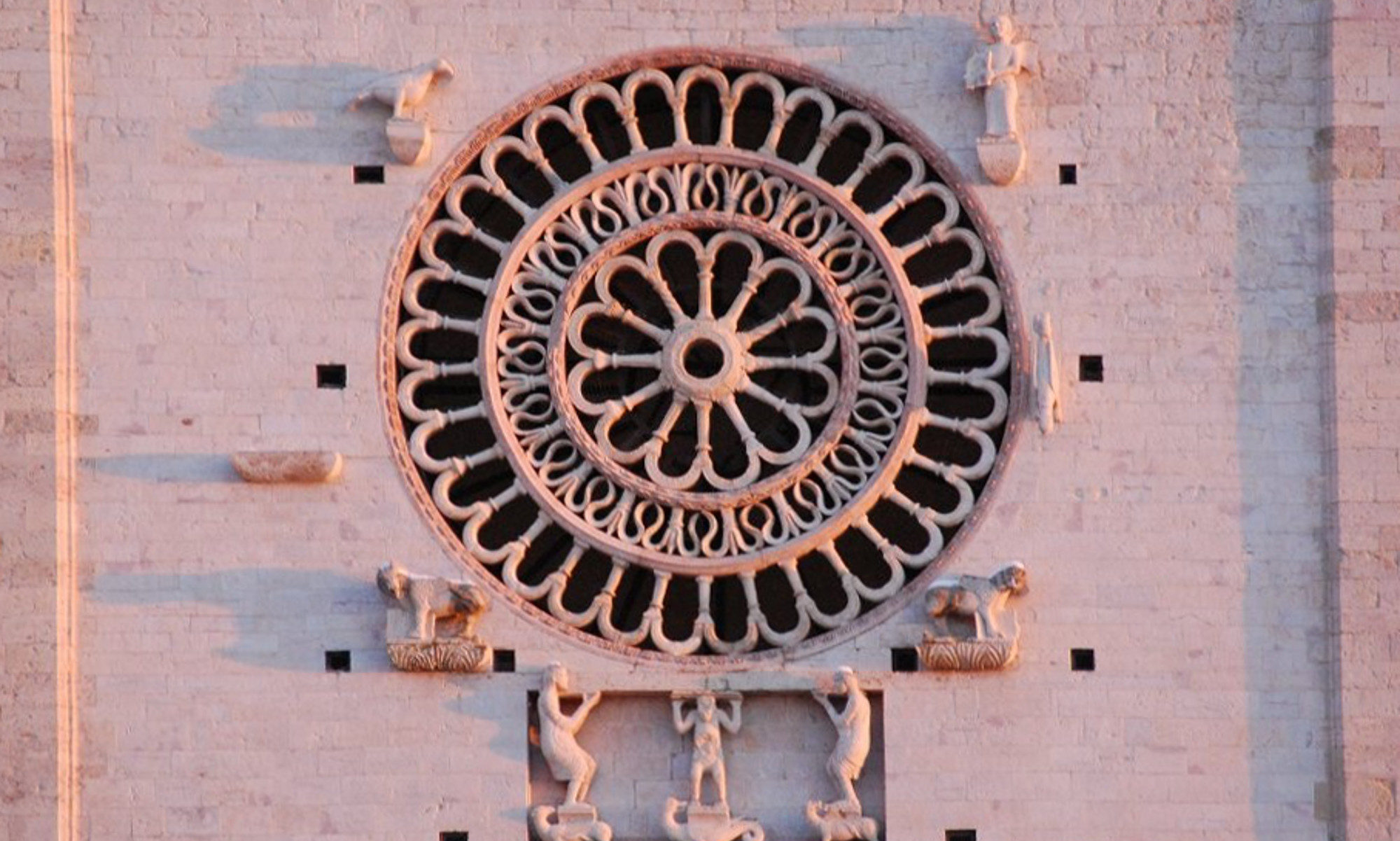

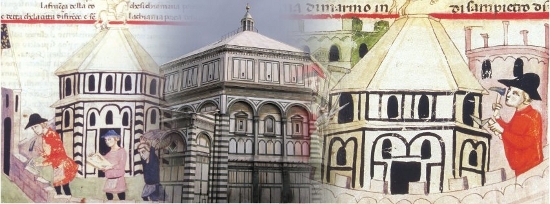

Most of the iconic features of Renaissance Florence, those familiar sights we can still visit today, didn’t exist. Not the mendicant churches of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella, nor the Bargello, nor the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Florence’s Cathedral in those days was Santa Reparata, a much smaller church on the same site. The Palazzo Vecchio was not yet built. Even the bridge we now call the Ponte Vecchio was different–the one my characters crossed washed away in a flood in 1333 and was replaced by the one that’s there today. Only the Baptistery was already there, and already ancient, when my story takes place.

Florence’s skyline was defined by towers belonging to the great magnate families. Lean, powerful, no-nonsense towers thrust into the sky, built for both offense and defense in the all-too-frequent bouts of urban warfare. Around 1250, a government composed of more guildsmen than nobles decreed that the pesky towers be shortened, to lessen the chance of violence on the part of the magnates, or the dangers of troublesome noble families jockeying for power. Yet stubborn little stubs of those towers are still standing, even after so much of the medieval part of the city was destroyed during World War II. Those things were built to last!

Alana: Isn’t that amazing? Actually, after a passage of 600 years, today Florence–the historic center–remains much the same as yesterday. That’s why we love it!

Tinney: Yes, we do. But your Florence is a lot easier to find these days than mine is. There’s still a medieval city lurking in there somewhere, but one has to wade through a lot of Renaissance and baroque stuff to find it!