Who is historical and who is fictional?

One of the first things readers of historical fiction often want to know is which of the characters really lived and which are invented for story purposes. Lady of the Seven Suns contains a mixture. Most readers will know that Francesco and Chiara (St. Francis of Assisi and St. Clare) are historical personages; fewer may realize that Giacoma is as well. Readers wishing to learn more about Giacoma but preferring to use English language sources may wish to look up Jacoba of Settesoli, as her name is anglicized.

Information given about the Frangipane family, about Francesco’s family, and about Chiara’s family follows the historical record for the most part.

Giacoma’s immediate family members (husband, sons, daughter-in-law) are historical, but her brother-in-law Cencio is not. The name “Cencio” recurs frequently in the Frangipane family, and some men of that name figure in the historical record, but this character is fictional.

All of the named high churchmen (popes, antipopes, cardinals) are historical. There was a recluse named Prassede who followed Francesco, though my character takes little from her besides her name.

Most named Franciscan brothers are historical. A reader who wishes to know more about Brothers Egidio, Leone, and Giannuccio from English language sources will want to look up Brother Giles, Brother Leo, and Brother John of Capella, respectively. Bishop Guido (both the first and second of that name) and messer Oportulo (podestà, or mayor, of Assisi) are historical.

Giacoma’s employees and associates (Vanna, Lucia, Amata, Massimo, Ricco, Donata, Bartola, Lapo, Renzo, Salvestra, Nuta, Sabina, Gualtiero, Feo, Belfiore, Mengarda, Arnolfo, and other more minor characters, as well as all the children associated with them) are fictional. Some early brothers did meet the fate described here for Ricco; the one biographer who lists their names does not include a Ricco, but since nothing else is known about those men, I chose to make my character part of that group.

Giacoma’s claim of a childhood friendship with Lotario Conti is fictional. She married into a family that certainly felt no friendship toward the Conti; still, her birth family (the Normanni) were not always politically aligned with the Frangipani, so I concluded it was possible, and adopted it for story purposes.

Lotario (the sheep, not the future pope) is, believe it or not, historical, though unnamed. Mousebane is fictional.

How much information exists about Giacoma?

Francesco’s first official biographer was Frate Tomasso da Celano, a Franciscan friar who was Francesco’s contemporary and almost certainly knew him personally. He wrote three works based on the saint’s life; Giacoma is not mentioned in all three, but Tomasso does cover her role in Francesco’s last days. St. Bonaventura (born Giovanni di Fidanza) was a Franciscan of the next generation who also wrote about Francesco and contributed to our meager knowledge base about Giacoma. Writings and utterances by Frate Leone and some of the other early followers, collected in volumes like the Assisi Compilation, give us a few more details and amplify what Tomasso and Bonaventura have written.

Some Franciscan scholars believe that Giacoma’s role in the early Franciscan community was suppressed or minimized, both by church authorities and by later generations of Franciscans. Tomasso of Celano’s first two biographies of Francesco, for example, where Giacoma is not mentioned, were commissioned by ecclesiastical authorities. This may have been out of fear that Giacoma’s relationship with Francesco might be misunderstood, considered scandalous, or might encourage overly warm friendships between friars and devout women, to the detriment of Francesco’s, Giacoma’s, or the order’s reputation.

Because Giacoma married into a prominent Roman family, extant documents pertaining to her property, as well as that of her husband and her sons, fill in the picture a little more. Even with that, the surviving information about Giacoma is scant and sketchy.

Names

In almost all cases I have elected to retain the Italian form of names, which these men and women would have used to address one another. The main exception to this rule was Brother Elias, whose Italian name (Elia) might have sounded like a female name to a reader unfamiliar with Italian nomenclature.

The Frangipane family name has an interesting history. This noble Roman clan proudly traced its origins back to Aeneas himself, and the surname is said to have come into being in the 700s, when an ancestor named Flavius Anicius Pierleone took it upon himself to relieve the Roman people’s suffering from a flood-induced famine by delivering bread to them, thus earning the name Frangens panem, or distributor of bread. And yes, this does show how far back the connections between the Pierleoni and the Frangipani go. They intermarried frequently, and their relationship was not always as contentious as it was in Giacoma’s time. NB: Frangipane is singular (the Frangipane family), and Frangipani is plural (the Frangipani).

Giacoma’s embroidery

Giacoma was a skillful embroiderer. Visitors to Assisi and Cortona can see examples of her needlework in the reliquary collections of two churches: the Basilica di San Francesco in Assisi, and the Chiesa di San Francesco in Cortona. Assisi holds an embroidered silk veil said to have been used to wipe the sweat from Francesco’s face in his final illness. Cortona is home to the cushion with an embroidered cover described in this book. The cover is red silk, embroidered in gold thread as well as green and yellow silk thread in a motif of heraldic lions and eagles, with additional figures of flowers and geometric designs. A local legend says that Giacoma gave the cushion, with its cover, to Francesco on his deathbed; an alternate tradition says that while she did give him the cushion at that time, the embroidered cover was added posthumously, when his body was transferred from its burial place in the Chiesa di San Giorgio to the newly readied Basilica.

Mengarda’s palazzo

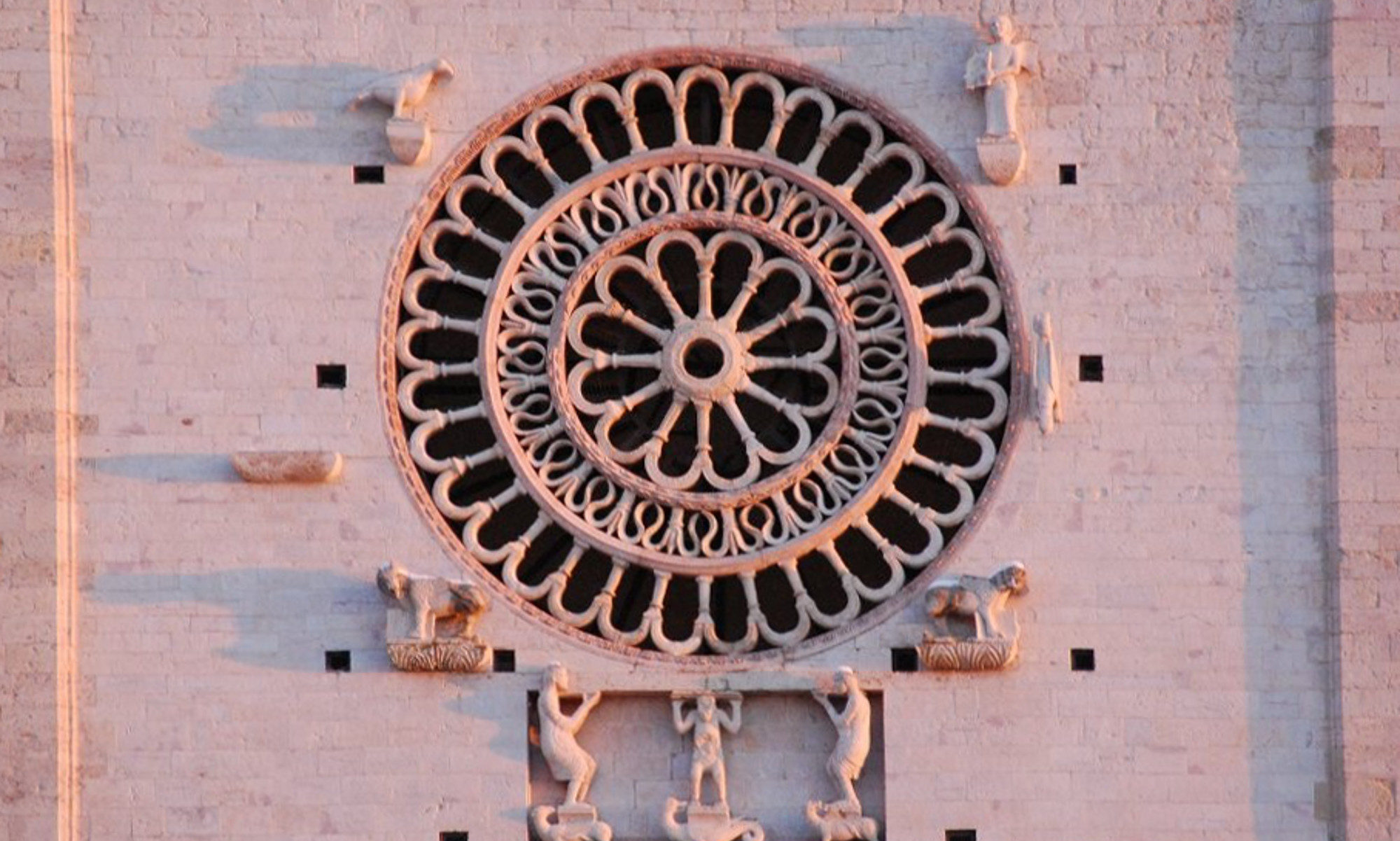

On a trip to Assisi some years ago, my husband and I rented a vacation apartment in precisely the spot I have given Mengarda’s palazzo. Thus, the view from the window, looking down to the left toward San Rufino, and the prized location just a few doors away from the house where Chiara grew up, are very precise in my mind. It was a privilege to be there, even if the wifi did decide to quit halfway through our stay. And I felt about the façade of San Rufino much the way Giacoma does in the book.

Miracle Boy

While the incident with the child and the oxcart is recorded in connection with that summer’s events at San Rufino, there is no record of the child beyond that point, so Miracle Boy himself is fictional.

Almond cakes

We know from the works of Tomasso da Celano that when Francesco dictated his letter to Giacoma from his deathbed, he asked her to bring a certain food that she had often made for him before. We learn from Brother Leone (in the Assisi Compilation) what that food was: a sweet made from almonds and honey. Some historians have interpreted this dish as akin to mostaccioli, a sort of Roman almond cookie. Others have associated it with the almond pastry cream used as a filling for tarts, cakes, and pastries, and called, appropriately, “frangipani.” Still others have concluded that it was marzipan, a rich sweet almond paste.

It is the custom in some Franciscan communities to mark St. Francis’s feast day by sharing a modern interpretation of these sweets. Thus, there are numerous recipes available online. I have made several of them–those that didn’t include blatantly modern ingredients–but I’d have to say my results were not entirely successful. But then, I didn’t have the advantage of Amata’s expert tutelage.

Fourth Lateran Council

My description of Pope Innocente III’s Fourth Lateran Council is taken from historical records, which include some fascinating eyewitness accounts.

Lamb

San Bonaventura tells us (Leggenda Maggiore) that Francesco presented Giacoma with a lamb, which lived with her, followed her around, and even woke her in the morning to make sure she would not be late for church. This creature’s name and personality are my invention. Author and sheep rancher Prue Batten advised me on ovine behavior, but any errors are my own.

Ugolino’s relic

Cardinal Ugolino, who was to become Pope Gregorio IX, did indeed wear the finger of a Belgian holy woman in a portable reliquary. I have treated the cardinal’s concern with blasphemy rather lightly, but historically it appears he went through a period when he experienced a crisis of faith, and that is when Jacques di Vitry presented him with this holy object. Jan Vandeburie, from the University of Kent, has written a paper entitled “When in Doubt, Give Him the Finger: Ugolino di Conti’s Loss of Faith and Jacques de Vitry’s Intervention,” presented at the 52rd Summer Conference of the Ecclesiastical History Society at the University of Sheffield, July 2014.

Bandits

Feo and his fellow bandits are fictional. The idea, however, came from one of the stories often told about Francesco, in which he and his brothers “turned the other cheek” when they were harassed by a gang of thieves, bringing their tormentors food, fuel, and clothing. This so disarmed the miscreants that some of them abandoned their thieving ways and joined the brotherhood.

Marino

Marino is a community in the Alban Hills, located about 13 miles southeast of Rome. In Giacoma’s day it was a Frangipani fief, and her family would certainly have had a residence there–Marino was, after all, a summer resort community for wealthy Romans all the way back to the Roman Republic.

An interesting document exists, dated 1237, in which Giacoma and her son Giovanni made a contract with her vassals in Marino, confirming their “consuetudini vigenti” (existing customs [habits, practices, traditions, conventions, possibly rights]). We don’t know what the issue in question was, but the document does tell us that in 1237 Giacoma was still very much the lady of Marino.

Mice

The mice that plagued Francesco in his hut at San Damiano are based on the historical record, as is his belief that they were a torment sent to him from the devil.

Ugolino and cats

Did Ugolino really hate cats? Here I’ve probably been unfair to the cardinal. The idea for his antipathy to Mousebane comes from his authorship (later, when he was Pope Gregorio IX) of the papal bull Vox in Rama, issued in the early 1230s. The bull condemned a German heresy that included a ritual involving kissing a black cat on the buttocks, among other strange practices.

Some have extrapolated from this that people began harassing and terrorizing cats as a result of Pope Gregorio’s words. It has even been claimed that a pogrom against cats allowed the rat population to surge and was thus the indirect cause of the plague that hit Europe in 1348. This appears not to be true. During this period, monks and nuns often openly kept pet cats—unlikely if the church had taken a stance against the creatures. Cats were valued for vermin control in many a medieval home and farm. Certainly there were times and places in the middle ages when cats were persecuted, whether for entertainment or out of superstition, but blaming it on Gregorio is a stretch. Still, that was the germ of the idea, and I turned the poor man into an ailurophobe. Apologies to Pope Gregorio for the liberty.

Peacemaking and the Canticle of the Creatures

The sequence of Francesco’s composition of the Canticle (the initial part, the verse composed to make peace between messer Oportulo and Bishop Guido, and the later and final verse) is as it happened. The Canticle’s role in making peace between the two warring dignitaries is also historical.

The translation of the Canticle here is my own, though informed by the work of many scholars.

Saracena

Saracena (birth family unknown) did marry Giovanni and was the mother of his two children, Pietro and Filippa, both of whom died very young, though they were predeceased by their father. Saracena remarried, acquiring two stepchildren. She apparently had inherited the use of the Septizonium and related properties, including the tower, for the remainder of her life. Records exist of sales transactions involving properties that had once been Giacoma’s and were being sold by Saracena. A historian describes her as “a woman of great vivacity of spirit and great ability.” Certainly she seems to have been a shrewd handler of money. Saracena’s relationship with Giacoma and her personality as depicted in this book are fictional.

Francesco’s death

I have told the story of Francesco’s last days and hours as accurately as I could, based on surviving information. Historical (or hagiographical) points include the letter to Giacoma; her appearance before the letter was sent; her explanation of why she arrived when she did; the revelation of the stigmata; the townspeople’s response; Elias’s gesture offering Giacoma the chance to hold Francesco’s body; and the flight of the larks.

Giacoma in Assisi

Giacoma did move to Assisi and end her days there following Francesco’s death, but this probably didn’t happen immediately, as I have written it. Some believe that she relocated to Assisi only shortly before her death, which probably occurred in 1239; this theory probably comes from her signature on the Marino document (see Marino above), although I believe that signature could have been made well after her move. Also indicative of a return to Rome perhaps several years before her relocation is a document naming her as tutor and guardian for her grandson Angelo, following the death of his father Graziano (Uccellino here) and, presumably, also the death of his mother. This latter document is dated 1230. While Angelo died very young, it does seem likely that Giacoma was based in Rome at least until 1230, but for story purposes I have had her make a more immediate decision.