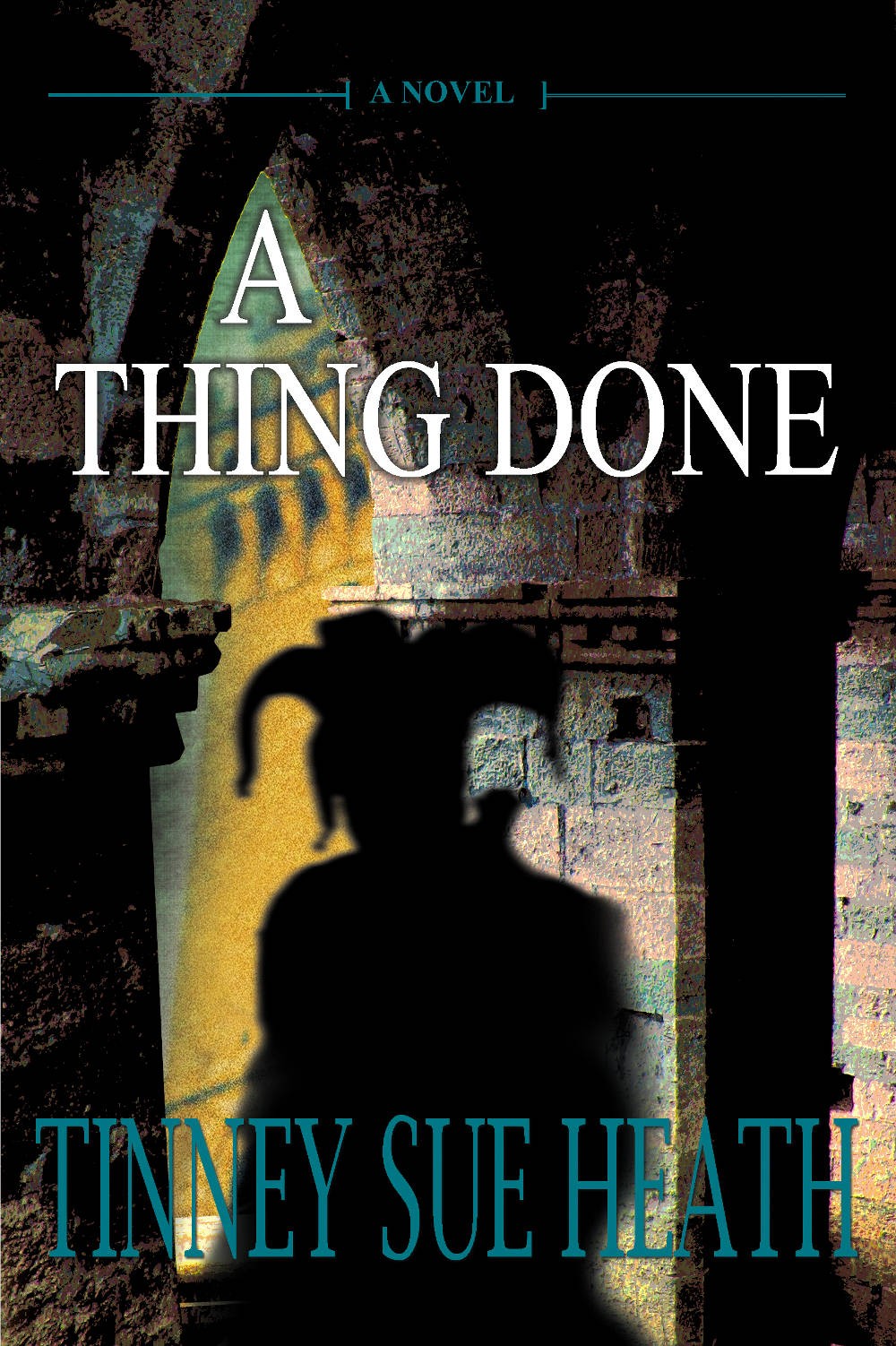

Subscribers to my newsletter (signup form is on the home page of this website) will have the chance to download my almost-unclassifiable collection of very short fiction based on the lives of seven women of Dante’s world. These vignettes, or character studies, are based on the historical record and/or on Dante’s writings, but the personalities and voices of the women are products of the author’s imagination.

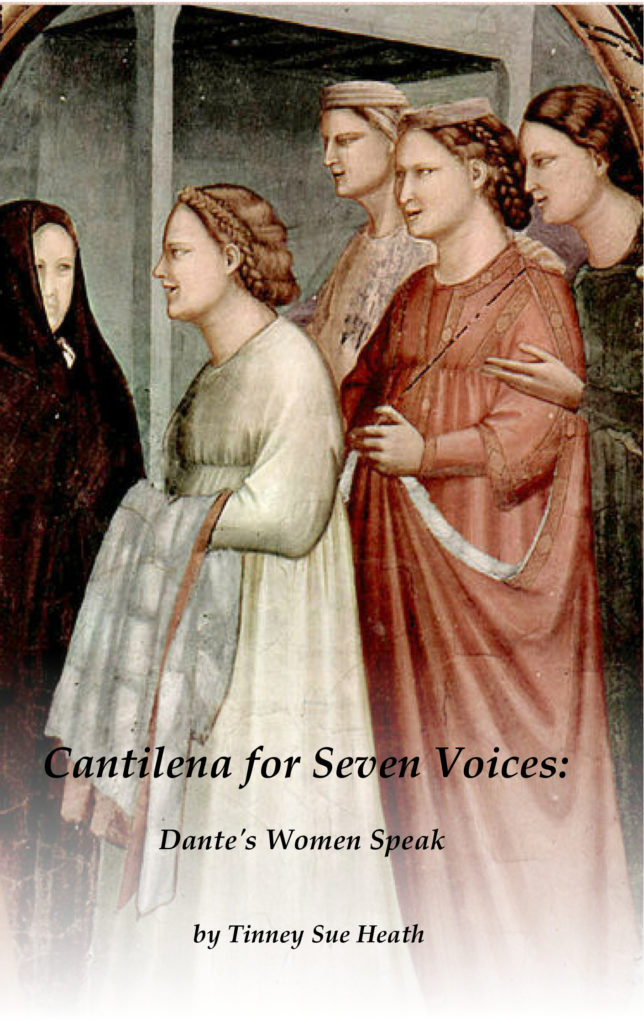

On this page you will find a collection of illustrations that will enrich the reader’s understanding of the city of Florence in the year 1300 and of the seven women featured in Cantilena. After the illustrations, you’ll see a lovely review of this book written by Canadian author Seymour Hamilton. Because this book is not for sale anywhere, it doesn’t accrue reviews as my other books do, so I was delighted to receive these comments, and I leave them here for you to enjoy.

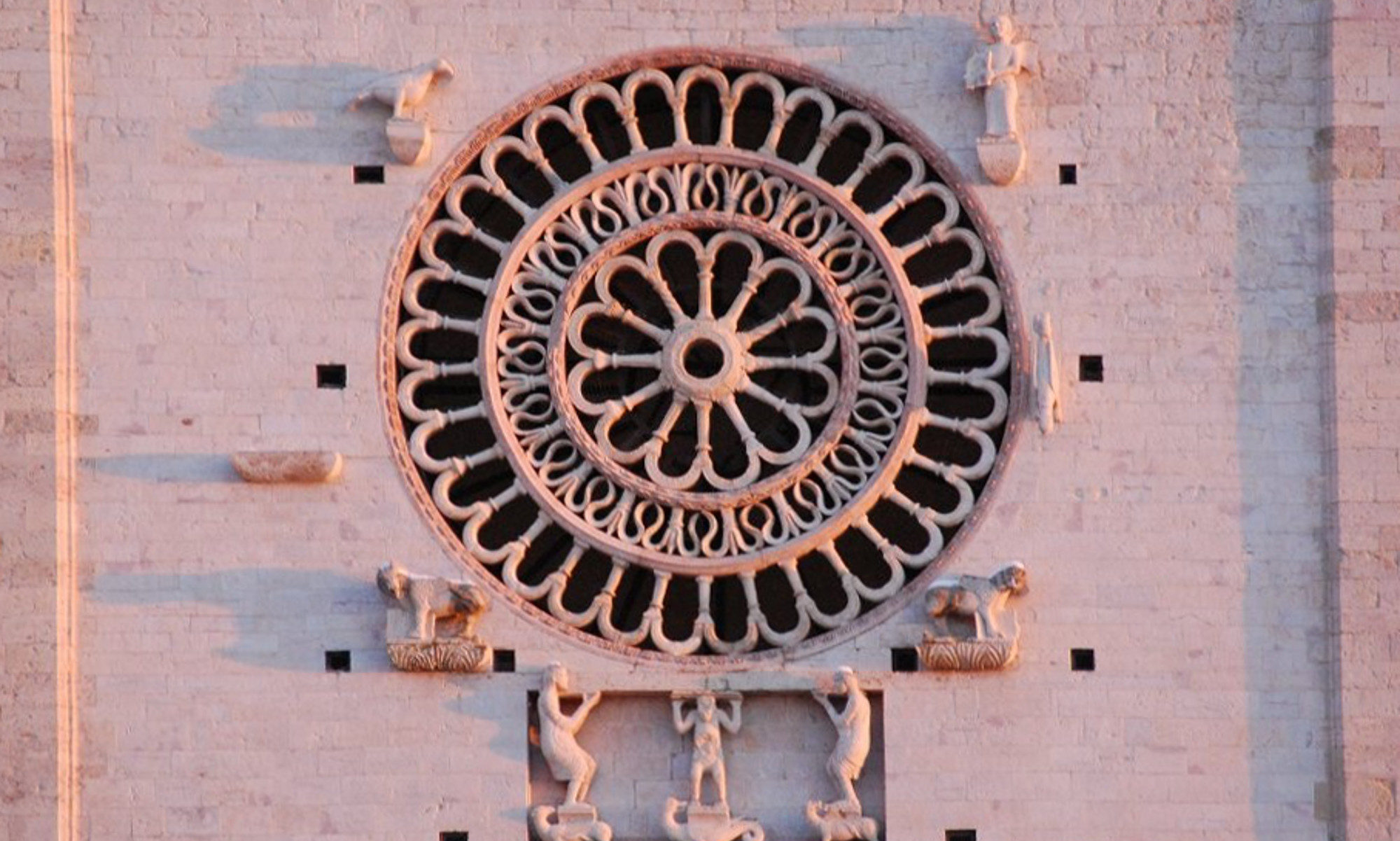

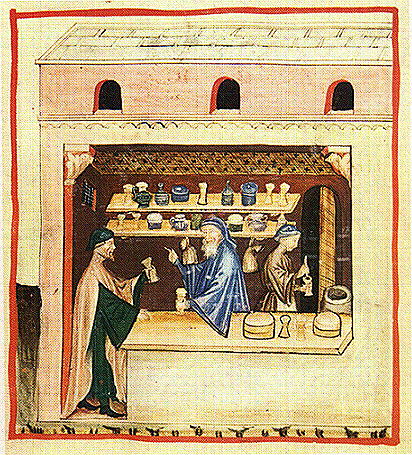

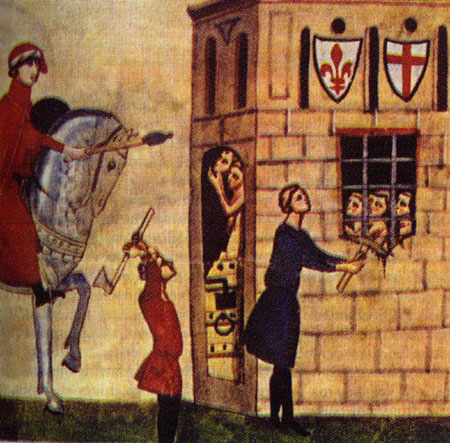

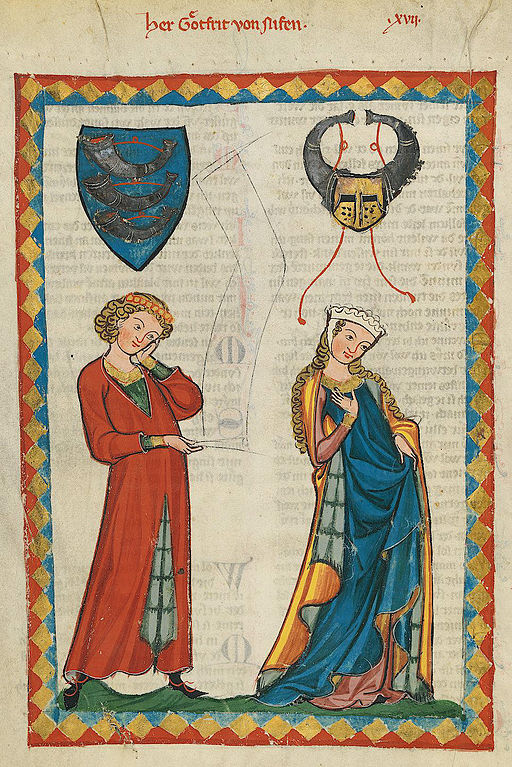

Florence, 1300:

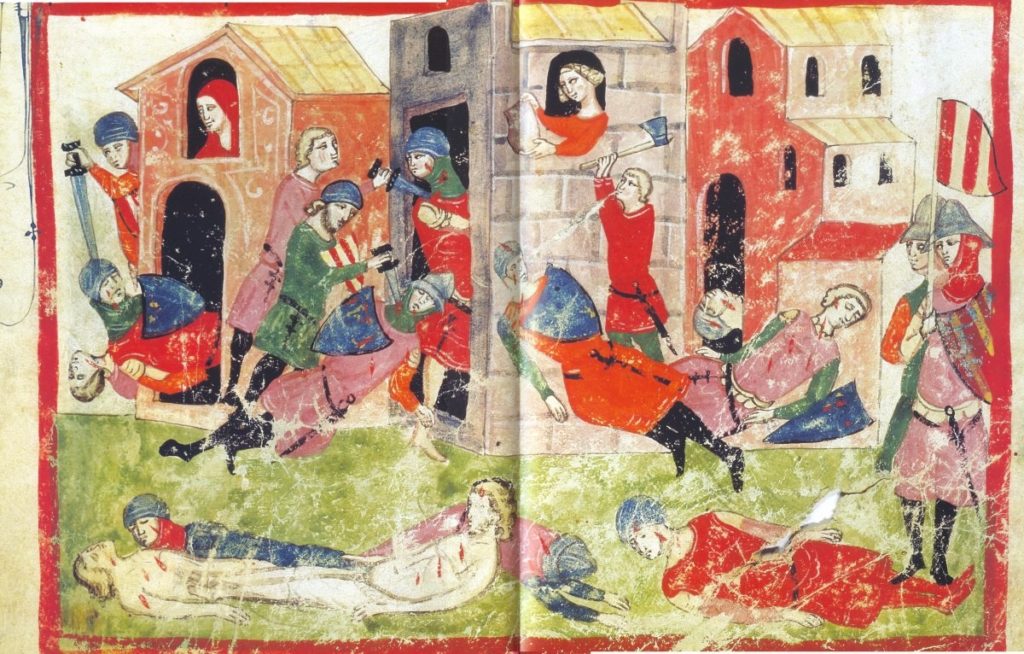

My concept of life in the Sesto di Scandalo, from The Illustrated Villani (14th century)

Cunizza da Romano:

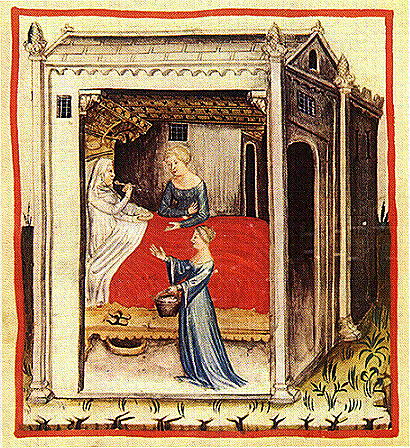

Nella:

Tessa:

Pietra:

Piccarda:

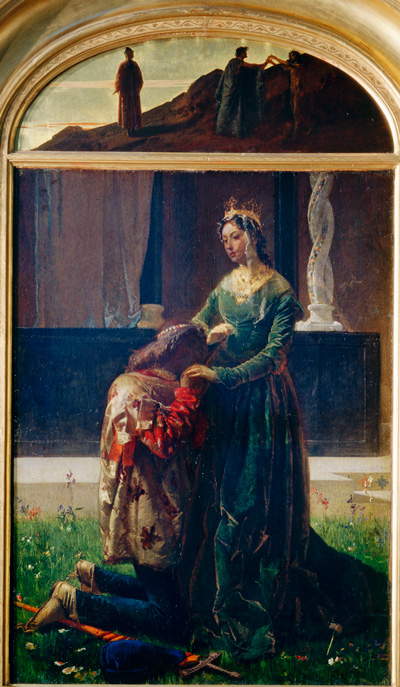

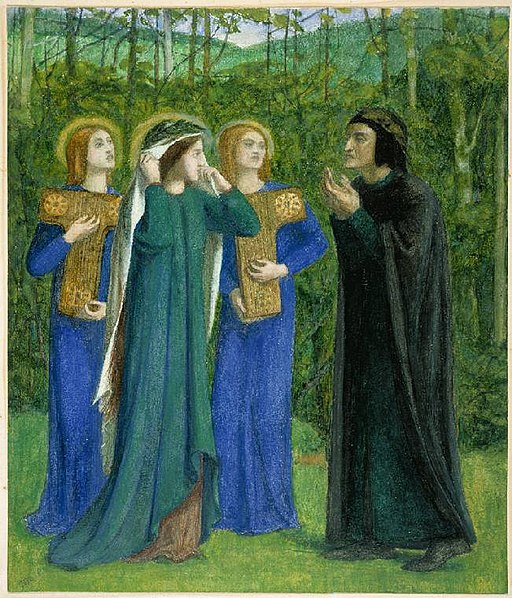

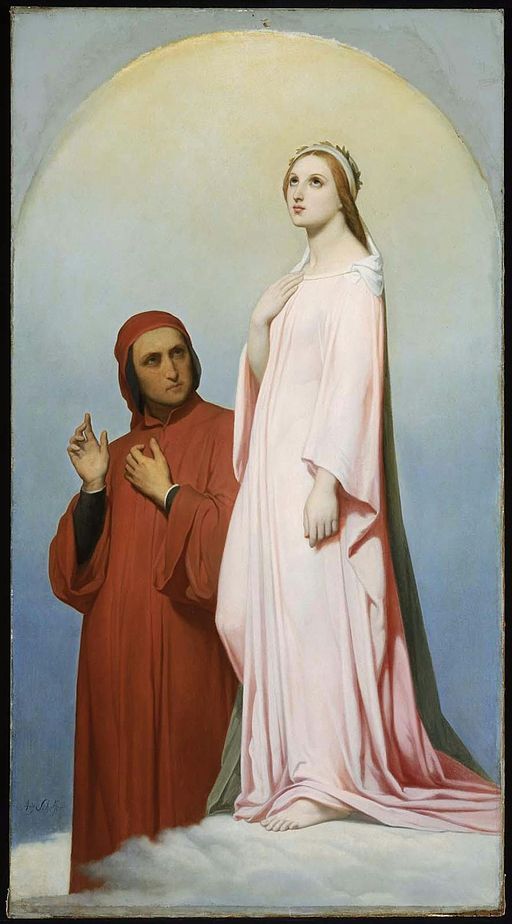

Beatrice:

Gemma:

Review of Cantilena by Seymour Hamilton:

One of the pleasures of retirement is to take a morning when the rest of the world is busy being busy, and read a book. If in addition the book in question is a delight in itself, the whole day is improved by the afterglow of thinking about a well-drawn character, savouring a well-turned phrase, recognizing that you share some of the author’s enthusiasms, for example Florence, Tuscany and history from the point of view of women.

I’ve just finished Cantilena for Seven Voices: Dante’s Women Speak by Tinney Sue Heath. and it is indeed a delight. More than that, this set of seven dramatic monologues is a literary tour de force. The idea of writing about the women in Dante’s life was a good one from the start, not least that in that in most cases, only a few tantalizing details of their real-life lives remain. Heath’s Cantilena is much more than just a good idea. Her writing takes seven historical figures and realizes them as individual women who speak to us in their own unique voices.

After setting the stage with a colourful description of Florence at the time of Dante, Tinney Sue Heath gives us the the beautiful, outrageous and unrepentant Cunizza, who talks to us of the young Dante to whom she spoke of her scandalous life, during which she ran through husbands and lovers like — and probably for the same reason as — Elizabeth Taylor. Cunizza only gets half a dozen lines in Dante’s thousands, perhaps because she was so well known in life, for among other things, having been the lover of the troubadour Sordello, who as a man and a poet got much more ink from Dante, and later, Robert Browning, and later still Ezra Pound, all of whom extrapolated poetry from Sordello’s life history.

Against all this testosterone charged literary history, we have Heath’s Cunizza telling us her story, and it’s by turns wry, insightful, a touch sardonic, and brimming with a life lived. She is the first of seven individual women who without Heath to give them voice, would otherwise be overshadowed by the men in their lives.

At the other end of the book is the saintly Beatrice who Dante adored, and Gemma his wife, about whom the greatest Italian poet wrote not one line. Heath makes Beatrice and Gemma friends, which is entirely possible, because they certainly were neighbours in that crowded little Florence of their time, long before the Ponte Veccio spanned the river Arno, or Filippo Brunelleschi built the dome of the church of Santa Maria del Fiore. Heath’s Beatrice is sweet but not cloying, beautiful, demure, and blithely unaware of her coming immortality as Dante’s guide to Paradiso.

In between are four more fascinating women, each with her own voice and character. Heath brings them all to life and lets them talk to us as if we had been spirited into their homes, to share a bottle of rich, red, truth-inducing Tuscan wine.

In vino, veritas, and in Heath’s writing as well.