A Thing Done – Author Notes

Florence in 1215

In that year Florence was in a period of intense growth, expanding from 15,000 to 90,000 residents between 1150 and 1250. Already an important city, she had not yet achieved the preeminence in Tuscany and in Italy that she was later to enjoy. Most of the familiar medieval landmarks (the Palazzo Vecchio, the Bargello, the mendicant churches of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella, the Badia as it is today) were not yet built. The cathedral was not the well-known Santa Maria dei Fiori of today, crowned with Brunelleschi’s famous dome, but a smaller, much earlier church on the same spot, dedicated to Santa Reparata. The Baptistery was already venerable, but the area between it and Santa Reparata was filled at that time with the tombs of prominent Florentines, many of whom rested in recycled Roman sarcophagi. Only one bridge spanned the Arno, in the spot where the Ponte Vecchio is now. The bridge present in 1215 had been reconstructed in stone after a flood in 1117 washed away the previous wooden structure. This bridge, in its turn, would be destroyed by another flood in 1333 and rebuilt yet again.

Houses, many of wood or a combination of wood and brick, were crowded together, with overhanging additions jutting out over the narrow and winding streets below. The city bristled with tall defensive towers, used in urban warfare. Yet even then, orchards and gardens existed within the city’s walls.

The Roman walls that enclosed the early city had been replaced by a new circle of walls, finished in 1177, which more than doubled the protected space. The walled area was to more than double again in the 14th century, when new walls would be built.

Florence was ruled by a podestà, a fairly short-term position which, since 1207, was always filled from outside the city to try to ensure impartiality, and by councils made up of her prominent citizens. Powerful families retained a great deal of control and influence, both as part of the governing elite and unofficially because of the money and military strength they commanded.

In the year 1215, Europe was in between the Fourth and the Fifth Crusades. The man who was to become known as Saint Francis of Assisi had gained papal approval for his religious activities, but his order was not yet officially recognized. Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor, who would be known as “Stupor Mundi” or the antichrist, depending on who was describing him, was a young man in the fourth year of his reign. The future Saint Dominic founded the Dominican Order. The Fourth Lateran Council had just established the doctrine of transubstantiation, and had forbidden the clergy to conduct trials by ordeal or by combat; elsewhere, Genghis Khan had captured Peking. In England in the year 1215, King John reluctantly sealed the Magna Carta. Dante would not be born for another 50 years.

Dates and Times

Chronicles of the events in this story split about evenly between assigning them to the year 1215 or to the following year. One reason for the confusion may be that medieval Florence began her year with the Feast of the Incarnation, March 25.

Time was relative. Daytime hours in winter were shorter than their summer equivalents. Bells marked the liturgical hours: Terce, the third hour, was about 9:00 a.m., and Sext, the sixth hour, around midday. None was not noon, as one might expect, but rather midafternoon, and Vespers rang at dusk. Florentines ate their main meal early, probably between Terce and Sext, and then took a light supper later in the day, after work was over.

Homes and Towers of the Elite Families

Stone buildings were the ideal, but brick with stone facing was not uncommon. Walls might be hollow and filled with rubble, and upper stories were often built of less durable materials than lower–brick above stone, or wood additions built onto brick. Overhanging jetties (sporti) jutted out from upper floors and gave people some much-needed additional living space. These were of necessity made of lighter-weight materials; still they constituted a danger to people in the streets below as well as anyone unfortunate enough to be in them at the wrong time, as it was not uncommon for them to collapse. Buildings might be joined to other buildings over the street level with balconies or passageways, blocking still more light from the street below.

Wall fireplaces and chimneys were rare at this time, if they existed at all. (Historians disagree on precisely when this improvement occurred and where it began.) Colder parts of Europe embraced this innovation sooner than the relatively mild Mediterranean countries, and a central hearth, with ceiling ventilation and with additional heating provided by portable braziers, was more usual. Kitchens were often in separate buildings, perhaps behind the house in a courtyard, or else on the top story, to minimize the risk of fire.

The towers so characteristic of medieval Italy were military in their original purpose. In their soaring height they demonstrated graphically a family’s might and wealth. Typically these towers reached a height of as much as 120 braccia (70 meters, or 230 feet). To put these dimensions in perspective, a building in New York, one of the skyscrapers of its day before it was demolished in 1955, was 82 meters (269 feet) in height and had 17 floors. Later, in 1250, the city government–briefly under the control of the popolo and not the elite families–decreed that private towers be reduced to no more than 50 braccia (29 meters or 96 feet).

These strong structures had massive walls, especially at their base. Towers as short as 39 meters (128 feet) have been found to have walls 2 meters (or over 6 1/2 feet) thick, narrowing to a thickness of 0.8 meters (over 2 1/2 feet) at the top. When a family found itself on the losing side politically, confiscation of its goods often included destruction of its towers, a symbolic as well as a practical gesture. In World War II, the German army destroyed much of Florence’s remaining medieval center with bombs, but not even twentieth-century explosives could destroy all of the towers. Damaged, truncated, but stubbornly still there, several of the mighty towers stand even today. The Amidei tower in this story is one that remains.

Towers were usually owned by a consortium, often made up predominantly of members of a single extended family but possibly also including their political allies. Shares might be as small as a seventeenth part or a twentieth, but membership in a consortium meant that one had the right to use the tower defensively. While it did not automatically mean that all other members of the consortium would actively come to a member’s aid in case of need, it did suggest that members would refrain from siding militarily against other members. Shares in a tower were inherited, but only by males, for a woman could marry someone who would one day turn against the consortium, and the risk of such a person obtaining the right to a share of the tower was considered unacceptable.

Names, Titles, and Heraldry

As the Jester’s comments about the “people with surnames” suggest, most Florentines at this time did not have a family name. Men were known by their first name and that of their father, possibly going back another generation if necessary for clarity (Neri di Giovanni di Ugo), and women were known by a first name and the name of a father or husband (Selvaggia di Lambertuccio degli Amidei).

All of the family names cited in this book did exist, and their affiliations were as shown. Oddo Arrigo dei Fifanti is sometimes elided to “Oderigo”. Berto degli Infangati is more traditionally called Uberto; I changed his name to avoid confusion with the Uberti family. Gualdrada was sometimes referred to as Aldruda; Isabella is called Beatrice in some histories; no one cites a name for Selvaggia, so I have provided her with one.

“Messer” designates a knight, “ser” a notary, and a married woman is called “monna”. Heraldic colors and devices were as I have shown them. The Buondelmonti did have a device which I have not described in the book, because I cannot find evidence that it was in use as early as 1215. It consisted of a stylized mountain (“monte”), which resembles three gumdrops, one stacked atop the other two, the whole surmounted by a cross (the “buon” or “good” in their name). It was in their traditional colors: white and blue.

Amadio

As the Fool suggests in the final chapter, young Amadio did indeed achieve sainthood, along with the six companions with whom he founded the Servants of Mary (Servites), of which order he was the third General. He was probably about twelve years old in 1215; for fictional purposes I have made him a little older, so he could take part in the events of this story. He is sometimes referred to as Saint Bartolomeo degli Amidei. He was beatified in 1717 and canonized in 1887. He did, as stated, make a pact with his companions that either all of them would be saved, or none of them. It is said that when he died, on 12 February 1266, the others saw a flame shooting up into the sky.

Danteisms

Two items in this story may be considered the author’s homage to Dante:

-

The Fool dreams his uneasy dream of a man whose hands have been cut off, holding up his bloody stumps. This is how Dante depicts the shade of Mosca, in the Inferno, where he is placed in the Eighth Circle among the Sowers of Discord.

-

One of the small children the Fool entertained at the Amidei house was the young Manente degli Uberti, later to be known as Farinata, the great Ghibelline leader memorably described by Dante, who places him in the Sixth Circle of Hell among the Heretics.

Marriage Rituals

Marriages in Florence during this time period consisted of three separate stages, stages which could occur very close together in time, or which might be separated by years. Betrothals of children, for example, might occur years before the ring-giving and the bride’s transfer to the husband’s home, and even once the ring was given, considerable time could elapse before the bride changed her residence–for example, if her father found himself unable to pay the dowry in full.

None of these ceremonies required the church in any way (though a nuptial mass could certainly be part of the later stages), but they did require witnesses, consent on the part of both spouses, and usually a notary to record the contract. A marriage, whatever else it might be or become, was first and foremost a business transaction.

Preliminary to everything else was the impalmamento, or handclasp, which sealed the agreement between families, an agreement which may well have been facilitated by a marriage broker or a family friend. It was not necessary for either bride or groom to be present for this agreement; it was strictly between the families, and the only essential ingredient was the presence of the man who had authority over the bride-to-be, her father or guardian.

Stage One of a Florentine marriage was the giure (general term) or sponsalitum (notarial or legal term): a binding betrothal ceremony with only males present. As many male friends and family members as possible gathered to witness this agreement, which included the specifics of monetary exchange, such as dowry, trousseau, and morning gift. The giure often took place quite soon after the impalmamento.

Stage Two took place at the bride’s home. Kin and allies of both sex and both families gathered to witness; the notary obtained the spoken consent of both parties, and the husband gave the wife a ring (the anellamento). He also presented gifts to the members of the bride’s family at this time, and they in turn played host at the feast that followed. After this ceremony, the couple was considered man and wife.

Stage Three completed the transfer of goods (dowry, trousseau, gifts, woman), and saw the bride transferred to the husband’s home via a public procession, to be followed by another feast at her new home. This stage was called the nozze.

At this time in Florentine history, consummation typically followed the nozze, but this was by no means an absolute. Customs could vary with time and place and level of society, so Buondelmonte’s wish to consummate his marriage with Isabella before the nozze was not necessarily inappropriate.

What the Chronicles Say

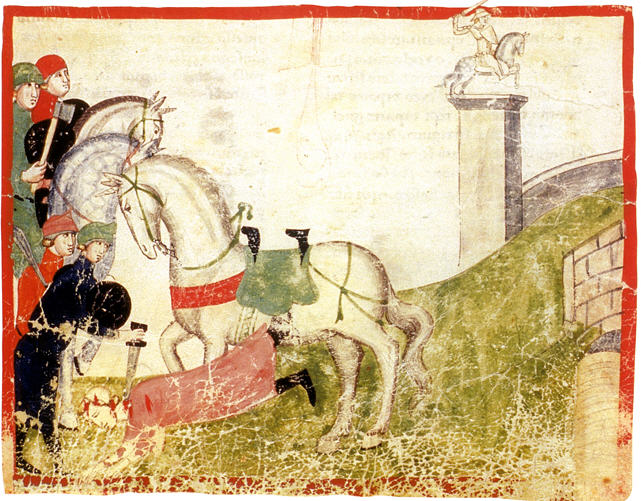

The earliest extant record of these events appears in the Chronica of Pseudo Brunetto Latino (so called because for a long time scholars thought it was authored by Dante’s contemporary Brunetto Latini, but then they decided it wasn’t), written at the beginning of the 14th century–that is, less than a century after these events took place. The banquet, the jester’s prank, the insult offered by Oddo, the injury inflicted by Buondelmonte, the ensuing councils and agreements, Gualdrada’s persuasion, Buondelmonte’s betrayal of his betrothal to the Amidei girl, and finally the vendetta against Buondelmonte and its outcome appear in this book very much as they are set forth in this and other early chronicles of Florentine history.

Later chronicles (Dino Compagni, writing in 1311; Giovanni Villani, writing in the 1330s; Marchionne di Coppo Stefani, writing in the mid-1380s) and histories (Machiavelli, in the 1520s) tended to begin the story with the broken engagement and say little or nothing of what preceded it. Taken together, the accounts demonstrate some uncertainty as to details: Did Gualdrada summon Buondelmonte, or did she hail him as he passed in the street? Did they already have an understanding, or did she present her lovely daughter to him then for the first time? Did the ambush take place on Easter Sunday or another day? Was it Buondelmonte and Isabella’s wedding day or after their wedding?

They agree that there was a daughter of Lambertuccio degli Amidei, and that she was jilted by Buondelmonte, but we don’t know her name, or how she felt about the things that happened to her, or what, if anything, she may have tried to do about it. Thus, the character of Selvaggia is my own invention, as is Mosca’s motive for influencing the council as he did–though the chroniclers unanimously give him credit, if credit is the right word, for his famous declaration: “Cosa fatta capo ha.” (A thing done has an end to it; or, Once it’s done, it can’t be undone.)

Later chronicles put greater or lesser emphasis on Buondelmonte’s guilt, according to their own political leanings, for the Guelf-Ghibelline split divided Italians for centuries after this incident. Villani, for example, says that Buondelmonte was influenced by the devil, thereby providing him with an excuse, and he places the greater blame on Buondelmonte’s enemies.

Oddo

And for anyone wondering how things played out for the redoubtable Oddo: The vendetta reached its tentacles far into the future. In 1239 the Buondelmonti and Uberti made a brief peace with the marriage of a daughter of messer Rinieri Zingari dei Buondelmonti to messer Neri Piccolino, brother to messer Farinata degli Uberti. Shortly afterward, the Buondelmonti faction lured the Uberti into a trap, and Oddo and a son of Schiatta’s were killed–by a Donati.